June was spent entirely at home in Montreal; it included an excellent Scintillation, the small science fiction convention for which I do program, and a week with a lot of friends in town. (Come to Scintillation next year! If you like this column, you’d enjoy it.) Other than that, the weather was such that I spent a lot of time sitting out on the balcony reading. I read twenty-five books in June. They were an interesting assortment, and some of them were amazing.

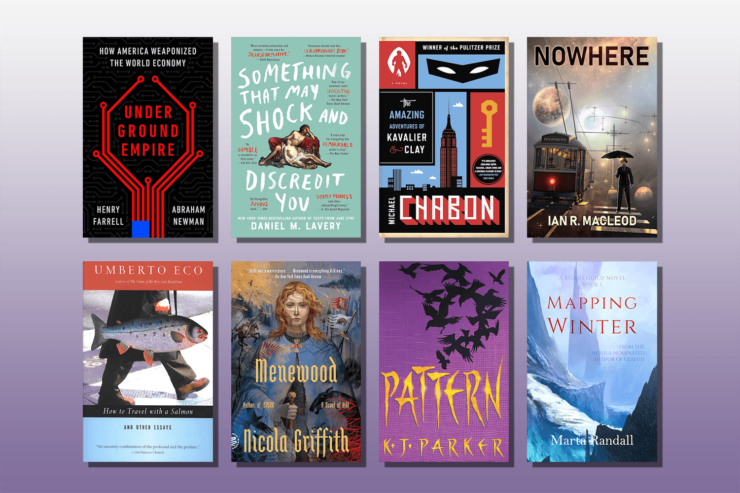

Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy — Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman (2023)

Riveting non-fiction book that dives deep into the internet, the world banking system, and international politics of the last few decades to link them into one evolving story. Although some of this stuff is highly technical, this is written so as to be not so much approachable as gripping. This is important, and I’m glad to see that the book has been winning awards. C.J. Cherryh has a line about the little piece of information that slots into place and suddenly illuminates the whole picture and makes things make sense. This book contains a lot of those little pieces of information.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay — Michael Chabon (2000)

Chabon is a terrific writer. There’s just so much in this book, it makes it very difficult to talk about. To start with, this is a book about a Jewish family in the 1930s, and you have to be braced for history. But what it’s essentially about is escape. Joe, a young man who has escaped from Prague one step ahead of the Nazis, and whose family has very much not escaped, creates a comic book hero—“The Escapist” —who fights fascism. His cousin Sammy, who is gay, and who grew up in New York, helps in this creation, and the two of them are involved in the early comics world and in WW2, and in falling in love with people, and then living on in the McCarthy era. None of it is predictable, and it all feels absolutely real.

Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life — Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachel Wiseman (2022)

Another really excellent and well-written book. Elizabeth Anscombe, Iris Murdoch, Philippa Foot, and Mary Midgley, together and separately overthrew the prevailingly fashionable philosophy of A.J. Ayer and others, in order to have a way of saying that some things are in fact objectively worse than others, like for instance fascism and the bombing of Hiroshima. They all went to Oxford around WW2 (making this an urgent necessity) when many of the men were away, which is itself interesting. The book draws on letters and diaries and interviews, and is fascinating, both about philosophy and about the everyday lives of the women. They were often bringing in ideas from non-Anglophone philosophers, like Wittgenstein and Sartre, which is (again) intriguing in its own right. I was pleased to see a mention of my late friend Gill Goodridge (to whom My Real Children is dedicated) from whom I learned so much about Oxford at this time. I’d been thinking about her as I was reading, and was delighted to see her briefly appear on the page! Well written, and generally a great book.

Menewood — Nicola Griffith (2023)

Sequel to Hild, and do read Hild first, whatever you do. This book is wonderful, but it begins with a lot of really terrible things happening. The first part of the book is a real downer. It rises from this low point and never approaches these depths again, but gosh, it was a lot. Also, it’s very long. But it’s worth every minute. Griffith really brings seventh-century Britain to life, every mouthful of food, every touch of cloth, every hidden cache of food, the way you butcher an animal, make food last, give a feast. Menewood has a lot of nation-building logistics, some fighting, some scheming, terrific characters, and a complex study of what power is and how it can be wielded by different people in this world. It’s better for not being fantasy, for being straight historical, but written using the techniques honed in genre. I always find Griffith intensely readable, and these two books taken together are a masterpiece. I hope she writes another volume, the space is there for it historically, and I’d be very interested, but whether or not she does these two existing volumes are something extraordinary.

Pico della Mirandola on Trial — Brian Copenhaver (2022)

You’d think I’d love this, wouldn’t you, with how interested I am in Pico, but in fact this is an attempt to show how Pico was a scholastic, and written in a scholastic way, and I got bogged down in the details of scholastic philosophy. It’s a detailed analysis of the book Pico wrote to explain why the thirteen (of nine hundred) theses condemned as heresy weren’t heretical at all. It’s as if Copenhaver wanted to make a case for Renaissance philosophy being as boring and rigorous as modern analytic philosophy, which he does quite well, but it wasn’t the book I was looking for. I suspect he wouldn’t like my Pico books either, but he’s (fortunately) unlikely to read them.

On the Beach — Nevil Shute (1957)

Re-read, bath book. Weirdly elegiac book about an American submarine captain and some Australians with less than a year to live after a nuclear war has wiped out the Northern Hemisphere and radiation is making its way towards them. It’s a very odd book indeed in that if you thought about what a book like this would be like it doesn’t have any of it—just people mostly in denial moving slowly through ordinary things. There’s a moment when they open the trout fishing season early so that people can get some last angling in streams in before they die of radiation sickness, because people wouldn’t have broken the law… but yet the characters feel real, and as if people really would act like this as the human race dies out.

It is SF, as much of Shute is. It’s most interesting to compare to What Happened to the Corbetts (1939) which is a prediction of the beginning of WW2 that was SF when it was written but now reads like alternate history. It gets a lot of things wrong but a lot of things right, in the fine-grained detail. Fortunately, WW3, that particular WW3, with the Soviet Union, can’t now happen, and the world and mores of the 1957 he was writing it in are also gone. I don’t really like On the Beach, and don’t really recommend it, but there’s certainly nothing like it.

P.S. I Hate You — Sophie Ranald (2022)

This is about a couple coming back together after giving up on fertility treatments, interspersed with how they got together in the first place. Set in Britain. Contains cats. It’s sufficiently well written that I kept reading, without being actually good.

How to Travel with a Salmon & Other Essays — Umberto Eco (1992)

Gosh this was good. It actually made me laugh aloud with surprise and delight several times. I feel as if I really like Eco as a human being after reading these short funny pieces, which have beautiful timing. They’d be wonderful to read aloud, and I may read one the next time I have a reading aloud party.

Celia’s House — D.E. Stevenson (1943)

Edge-of-genre in a weird way. This is a strange book which begins with an elderly lady leaving her house to a future daughter (as yet unborn and unconceived), of the nephew who didn’t expect to inherit, and then her ghost overseeing his family in her house until she is reincarnated as the daughter. It then abruptly becomes a version of Mansfield Park with the other characters for a while before catching up with itself, in 1943, and having an odd kind of end during WW2. Like most Stevenson, it’s an enjoyable read, but I’m not at all sure what she thought she was doing with this. It’s interesting to consider the kind of genre elements you can put in a mainstream book and get away with it, ghosts and reincarnation being fine, apparently. It’s the opposite of Menewood in a way, which is straight historical fiction but using genre techniques and expectations; this is using genre elements but very much mainstream techniques.

The Pursuit of the Pankera — Robert A. Heinlein (2020)

I bounced off this when it came out in March 2020, saying “I didn’t like this book last time when it was called The Number of the Beast and you can’t make me read it again.” However, reading it now, it’s interesting to consider that Heinlein wrote this book and then revised it into The Number of the Beast (NoB), which is considerably worse. Neither of them are good books, don’t get me wrong, but this isn’t as awful as the book he decided to publish. They both start the same way, and go on the same way for longer than I could stick it at the beginning of the pandemic. A mad scientist, Jake, has invented a continuum-jumping machine, his beautiful daughter, Deety, tangoes with someone they think will understand the math, Zeb, but they’ve mistaken him for his cousin, and the three of them run off with the hostess of the party they met at, Hilda, get married, and have adventures in other universes while being pursued by aliens trying to kill them.

The plot with the aliens, here called pankera, makes actual sense in this version, unlike in NoB. The books diverge after the dissection of an alien. The Pursuit of the Pankera (PP) is essentially fanfic from that moment on, in which the four improbably excellent central characters visit Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom, Baum’s Oz, and E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lens, and do the whole “what these people need is our heroes” thing. NoB also does universe-hopping but only briefly strays into other people’s universes. PP has a lot less of the annoying things about NoB, less of Deety’s nipples, and none of the super-annoying “who will be captain?” thing. I don’t know why Heinlein rewrote the book and made it worse, except that there may have been copyright issues with Burroughs and Doc Smith, and someone may have pointed this out. Anyway, PP is not a good book and not worth your time, and NoB is worse, but the two of them are interesting to consider together if you’re interested in Heinlein, in terms of how and why he revised and what he changed.

Something That May Shock and Discredit You — Daniel Mallory Ortberg (2020)

A trans memoir. Ortberg used to write for The Toast and the parts of this that work best are at that kind of short blogging length. This came highly recommended, and I found it generally interesting but not mind-blowing.

Mapping Winter — Marta Randall (1983)

Re-read, bookclub. When I first read this I said to myself that I was going to save re-reading it for when it was hot, and it genuinely cooled me down to read this in a heatwave. This is a very unusual book, especially for when it was written. It’s a fantasy with no magic, set at a time period when a feudal world with oaths and guilds is changing because of pressure from railroad and telegraphy. It’s a portrait of a woman who is between cultures, and who has survived abuse, and who is fiercely bound by her oath even when it leads her into doing evil.

Baby Proof — Emily Giffin (2006)

Re-read. I probably read this from the library in 2006 or not long after, because I’d forgotten pretty much everything about it except the protagonist’s absolute determination not to reproduce. I wouldn’t exactly call this an unreliable narrator, but it is definitely first person of a person I do not like and find unsympathetic.

Selections From Modern Poets — J.C. Squire (1927)

Fascinating collection, in alphabetical order, of selections from poets who Squire (who I mainly know as a Celtic specialist) thought were important. No Eliot, too early for Auden, some of the Great War poets I know and some (some great) I did not, lots of Walter de la Mare (who I loved as a teenager) and Belloc—but a very different selection than if someone made a selection of poetry from the first quarter of the twentieth century now. Thoroughly enjoyable, even the bad bits, and free on Gutenberg.

Nowhere — Ian R. MacLeod (2019)

The second volume of Ian MacLeod’s collected stories. Gosh he’s good. I want to say he’s underrated. He does get nominated for awards but I don’t think he gets talked about enough, probably because his best work is all at novella length. There are a number of stories in here I’d read before and remembered well, and a few that were new to me and blew me away. He does idea stories and gives them flesh and blood. He reminds me of Sturgeon in a way. He’s one of the best people writing science fiction at the moment, and you want to read this if you haven’t already.

The Making of a Prig — Evelyn Sharp (1897)

Having run across mention of Sharp as a suffragist and children’s writer, I downloaded this only to discover that it had more in common with Somerset Maugham than Angela Brazil. To me, and my familiarity with the between-wars period, “prig” seems like a term used by and of children, but I was very wrong, in 1897 it was used of adults, though the meaning remains somewhat obscure to me even after reading the book. It’s an interesting story of a vicar’s daughter who goes to London to earn her living, finds it difficult to get started, falls in love with one man and is beloved of another, and negotiates both men and a career to a happy ending. If it were written now it would be a very different book, both more and less feminist, and I’d have entirely wrongly criticized the economic opportunities available at this particular moment of 1897—so different from either ten years before or ten years after. History smushes things together. This book had way too much angsty love for me, but it was interesting to see a young woman (shockingly) visiting a man in his rooms and knowing where to get cream on a Sunday. I’ll probably read Sharp’s fairytales, and she’s certainly a fascinating person.

Dante: The Story of His Life — Marco Santagata (2012)

Biography of Dante that has rather more “he must have felt” and reading in reality from his fiction than I prefer. However, there was quite a lot of information that was useful. I don’t really recommend this for general interest, though.

Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things — Lafcadio Hearn (1904)

Lafcadio Hearn was an incredibly fascinating person, who looked at the whole world with an outsider’s eye. This is a collection of Japanese ghost stories that he wrote in Japan, mostly told to him by his Japanese wife, then retold by him in English. Some of them apparently are classics in Japan, translated into Japanese. It’s really interesting to see how his Western (he was Greek-Irish) sensibility changed some things, and easy to see why this was many people’s introduction to Japan at the turn of the twentieth century. There’s also a strange section about insects. These are great, and I’ll definitely read more.

The Italian’s Inexperienced Mistress — Lynne Graham (2005)

This was really bad. They hardly go to Italy at all in it, and even when they do it’s barely described. This is a kind of billionaire romance, with revenge and true love and lots of passion and sex. I don’t really want to read revenge romance about people who don’t like each other but are compellingly attracted, in fact I find it kind of weird.

One Art: Letters — Elizabeth Bishop (1995)

Collection of Bishop’s letters, edited by Robert Giroux, from her college days to her death, very long, it took me more than a year to read. I’d previously read the letters between Bishop and Robert Lowell. I like reading letters, and I like reading letters of working writers. I never really felt close to Bishop, though she’s interesting, a lesbian with disabilities (severe asthma) and an alcohol problem who lived a lot of her life in Brazil while being really thoroughly acclaimed as a poet in the US. But even after spending a year reading thirty years of accumulated letters to other writers and friends, I still feel at arm’s length, unlike with Petrarch and Sylvia Townsend Warner and George Sand and dear Cicero… Not sorry I read it, but kind of glad to be done. I welcome suggestions for collected letters available as ebooks.

Pattern — K.J. Parker (2002)

Second in trilogy, don’t start here. Lots of this book is about being a person who can’t read minds or have his mind read surrounded by a community where it’s normal. Lots of it is about building a house and using a forge and dealing with a natural disaster (volcano) and diverting a lava flow from a volcano. Some of it is about metaphysics and crows. All of this is excellent. Unfortunately, Parker doesn’t seem to think a book is worth typing if it doesn’t have killing people in it, and so there is also some of that. On the whole I enjoyed it and, as usual with Parker, found it compulsively readable.

The Book of Sanchia Stapledon — Una L. Silberrad (1927)

Bath book. Terrific historical novel about a girl printer in Kendal in 1687, with rebels, poisoners, dissidents, gaol fever, cousins, beautiful schemers, stone circles, secret hiding places, and sensible people who like each other. Also, when you consider how many books there are where people are working for Bonnie Prince Charlie, it’s refreshing to read one where someone is working for the Glorious Revolution and William of Orange. Unfortunately there isn’t much Silberrad available. I bought this as a used hardcover and had to put it into Goodreads myself. Read The Good Comrade.

Rooftoppers — Katherine Rundell (2013)

Rundell wrote a biography of John Donne that I very much enjoyed, and when I looked at what else she had written I found this slight but charming children’s book. It’s a little vertiginous, but I enjoyed the Paris rooftops at midnight. There’s nothing fantastical in this, in a genre sense, but this is the genre where babies are found floating in cello cases after shipwrecks and brought up by absent minded professors.

A Year in the World — Frances Mayes (2006)

Travel book about trips Mayes has taken. I liked the bits in Greece and Italy best, but she also goes to Morocco, Turkey, Portugal, Spain, England, and Scotland. Everywhere she looks at gardens, eats food, and makes friends, so the book is easy to enjoy. She’s a good storyteller, and she manages that memoir trick of making you feel she’s sharing the important things. My favourite bit was where she goes to Mantua for the weekend and looks at the castle and eats and thinks wow, I live in Italy, I can just go to Mantua for the weekend, and there are all these other places I can go for the weekend, what a plenitude of joy…

The Lifted Veil — George Eliot (1859)

Remember when I said George Eliot should have written SF? Here she is writing a weird fiction novella about a man who can see what almost everyone is thinking and has precognitive flashes. It makes him very unhappy. The whole thing is written in Eliot’s inimitable style, though this is a very tight first person, and it feels absolutely believable. This isn’t in the category of the kind of genre elements you can have in mainstream fiction, even though telepathy and precognition can be that; this is something that’s been thought through, with consequences and psychological reality. It’s interesting to compare with Pattern in terms of how smoothly both Parker and Eliot write mindreading and sympathy. She totally should have invented SF, she’d have been great. Not a cheerful read, but really excellent.

Does the fine print on the Randall say anything about it having been published as The Sword of Winter? That’s what this book sounds like (from memories of decades ago).

I’ll have to look up the Parker trilogy; “compulsively readable” sounds good.

If you haven’t read any Parker and want to, start with the collection Academic Exercises or the novel Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled Castle.

According to the book description on Goodreads and Amazon, the Randall novel (Mapping Winter) was originally published as The Sword of Winter but “has been extensively revised to fit the author’s originally intended vision”.

Have you ever seen the movie of Kwaidan? I saw it maybe 50 years ago and I’ve never forgotten it, one of the most beautiful films I’ve ever seen.

I have not seen the movie. To a first approximation, just as often as the answer to “have you read” is yes, the answer to “have you seen” is no — I read a lot, I consume very little media in other forms.

How to Travel with a Salmon is great fun!

Rooftoppers is very good, though the middle-grade novel that Rundell’s been winning awards for is the recent Impossible Creatures, which I haven’t read yet, but which has been drawing comparisons to Philip Pullman.

I think The Lifted Veil is the second Eliot story I read, after Silas Marner. I saw it used somewhere and realized it was (kind of) SF, so I grabbed it. It is indeed very good,

Kavalier and Clay is amazing, and everything Chabon does is at least very good.

Also, I have a short piece upcoming in F&SF about Silberrad’s The Affairs of John Bolsover.

For anyone interested, Black Dragonfly provides an interesting novelisation of Lafcadio Hearn’s life.

E-book letter collection: Penelope Fitzgerald’s “So I Have Thought of You.”

I’m now reading it and really enjoying it, thank you so much for this suggestion!

Added to my list, thank you!

So….I love older historical novels about the 17th and 18th centuries, and I really want to read “The Book of Sanchia Stapledon”! Did you buy the last copy on the internet? There’s nothing on Abebooks or Amazon or Ebay, it’s not digitized on archive.org or hathitrust.org or Google books. It’s not even in Worldcat, which seems incredible to me!

The book seems to be out of copyright in Canada (author died in 1955) and also in the US. I don’t suppose there’s any chance you could scan your copy and make a PDF? This surely ought to be on Gutenberg…

Since Jo introduced me to Una Silberrad via this blog, I’ve been trying to track down more of Silberrad’s books, ideally with a plan to digitize them.

Getting books up onto Project Gutenberg is… well, a Project in and of itself, and I am slowly working my way through the documentation and have signed up as a content provider. At some point I hope that I can find a project manager over there who is willing to work with me, and get approval to start scanning the Silberrad novels I’ve bought that are not currently available anywhere online (there are quite a few on the Internet Archive) so that they can be proofread by the hardworking volunteers and (eventually, one day, I hope) made available for download on PG.

None of this really helps with the complete lack of copies of The Book of Sanchia Stapleton online, unfortunately, but it’s a start!

i assume you have approached the people at Distributed Proofreaders, which feeds material to Project Gutenberg? It should be fairly easy to find someone willing to scan and project manage. However, a word of warning: it takes a very long time for projects to make their way through the site. Several years as a rule — some of the five stages have a lack of volunteers able to work at that level.

Since the books are out of copyright in Canada as well, the other option is to approach Distributed Proofreaders Canada, where throughput times are shorter — a couple of years perhaps. Titles can be cleared for both (I take it you have discovered the clearance process at PG US, so they end up both there and on fadedpage.

(for clarification: I have been a project manager on both sites, though I now focus on the Canadian site)

I… may have bought the last copy on the internet? It wasn’t even expensive! I don’t think I could scan it, but I’ll ask friends about the practical options.

There are companies you can send your book to per post and they will scan it for you.

My very thoughts! Thank you for saying them.

The gentlest possible shove to read either of Suzanne Marrs’ collections of Eudora Welty’s letters. I myownself like William Maxwell more than I do Ross Macdonald so

What There is to Say We Have Said would be first if I’m directive about it. I think the letters, in both collections, offer so much quiet enjoyment and welcome respite from the endless shouting of this moment in time.

I’ve read both of those, and enjoyed them. I also really like Maxwell’s correspondence with Sylvia Townsend Warner.

It’s certainly interesting to read On The Beach now. I saw the movie about the time it came out (which would mean as a pre-teen, oddly enough) and I only read the book lately (2022). The movie left a lasting impression. I would recommend Kurosawa’s film “I Live in Fear” for an interesting approach to the general theme. And a tip of the hat and a word of thanks to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanislav_Petrov and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasily_Arkhipov. Perhaps at some point we should rededicate the Thanksgiving holiday to them, for our rather narrow escapes.

I have only read On The Beach once when I was about 15. I read through the night in deep silence. As I finished i opened the curtains to see that there was still a world out there (dawn reflecting on the windows across the snowy valley). It had a profound effect on me but I have never wanted to revisit the tragedy.

I also have been unable to reread Golden Witchbreed/Ancient Light for much the same reason, or The Eye of the Heron.

I anticipate there will be a Donna Leon and a Penric & Desdemona novella in next months reading list.

Also, loved The Homemaker from last month. Thank you

You know what I like! You’re not at all wrong, I read both the Leon and the Penric pretty much instantly on release.

Ancient Light is a book I try to forget about. I’ve come to the conclusion Gentle is a very good writer who just isn’t interested in writing the kind of books I’d enjoy. But if I could forget AL, I could read GW again.

Jo – I read Descent, the latest Marko Kloos Palladian Wars book – it was enjoyable but lots of open issues left to be addressed in the next/final book. Hope you can get to it in the August review.

You guys know what I like. I’m reading Descent now.